|

||

Day 1 |

||

|

||

Day 2 |

||

|

||

Day 3 |

||

|

||

Day 4 |

||

|

||

Day 5 |

||

|

||

Day 6 |

||

|

||

Day 7 |

||

|

||

Day 8 |

||

|

||

Day 9 |

||

|

||

Day 10 |

||

|

||

Day 11 |

||

|

||

Day 12 |

||

|

||

Day 13 |

||

|

||

Day 14 |

||

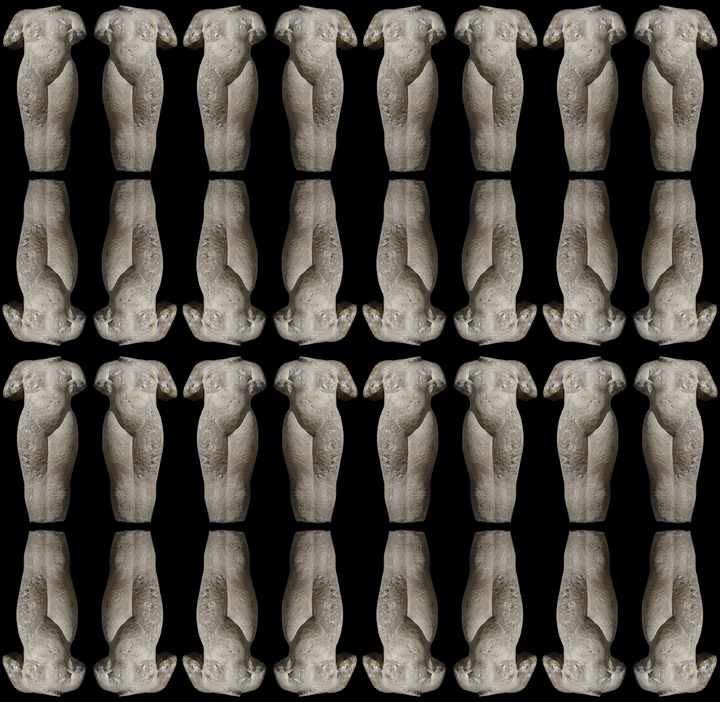

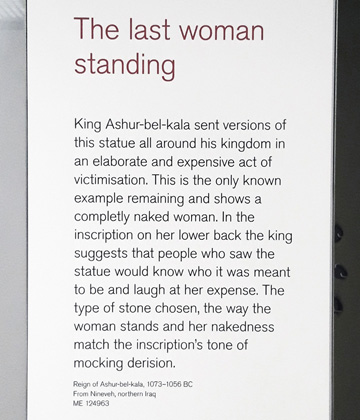

The last woman standing, Assyrian Statue, British Museum #124963, limestone, 93cm height, 11th C BC |

||

|

||

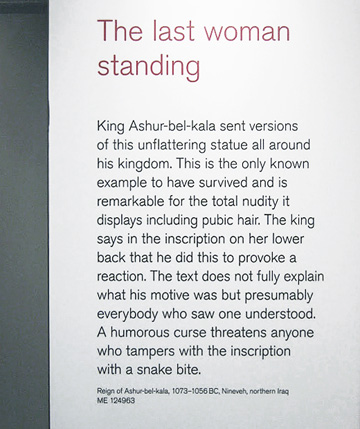

Wall text installed 2016 --------------------------------------------------------> Wall text updated in 2019 |

||

Colleen Heslin British Museum Thursday March 3, 2016 An open letter to the British Museum To Whom It May Concern: I was recently visiting the British Museum in February of 2016 and came across a remarkable statue, The last woman standing (British Museum Number 124963). I am interested in more information on the title and background of this statue, if you could provide me with any relevant historical and academic texts that reference this statue I would greatly appreciate it. I have done some basic online research and I have come across a limited amount of information, most importantly the recent translation of the inscription on the lower back on this work from 1991 and some descriptive notes in the British Museum online archive. However the title of the work, The last woman standing, does not seem to follow the statue in other text and references, it seems to only exist on the wall didactic in the museum. After reading the wall didactic that accompanies the work I was left with more questions then answers, and upon further research I found some of the British Museum wall text contradictory to other brief sources easily available. Could you provide me the name of the author and date of the didactic text? My suspicion is that the didactic text is old, perhaps poorly translated and simply needs to be revisited and updated with current and more accurate references to the translated text inscribed on the work. The wall description in full reads: The last woman standing However the description in your online database reads: The statue has an inscription on her lower back has been translated twice, once in 1902 by, E. A. Wallis Budge and again in 1991 by Albert Kirk Grayson. E. A. Wallis Budge’s English translation of inscription from1902: The palace of Ashur-bel-[kala, the king of hosts, the mighty king, the king of As]syria, the son of Tiglath-pileser, the king [of hosts], the might [king, the king of Assyria], the son of Ashur resh-ishi, the king of hosts, [the mighty king, the king of] Assyria. These ...[among the rulers] of cities and ... upon ... [have I ...]. Whosoever shall alter my inscription or my name (which is written therein), may the god Za[..] and the gods of the land of Martu smite him with ..smiting! (Property of) the palace of Assur-bel-[kala, king of the universe, strong king, king of As]syria, son of Tiglath-pile- ser, king of [the universe], strong [king, king of Assyria], son of Assur-resa-isi (who was) also king of the universe, [strong king, king of] Assyria: I made these sculptures in the provinces, cities and garrisons for titillation. As for the one who removes my inscriptions and my name: the divine Sibitti, the gods of the west, will afflict him with snake-bite." The main contradiction that I am finding in the wall didactic is the description of the statue as ‘unflattering’ and made for a purpose by the King, however that purpose is unknown but was understood by the Assyrian people. This vague reference to the inscription is uninformative and the public would be more accurately informed to read the current translated inscription in its place. While the Museum’s online database states that, ‘the King erected it for the enjoyment of the people’. I find it curious that the reason for the erection of this statue is known in the brief database notes, but unknown on the public wall text within the museum. What is agreed upon in both British Museum texts is that the King erected the statue; there is an inscription on it and great attention to the detail of the pubic hair. The most confusing word in the wall didactic is ‘unflattering’ to describe the statue. Is this word used to describe the statue as a sculpture unflattering, or the female form carved and represented as unflattering? Who perceives this as unflattering, the Assyrian people or modern western audience? I am struggling to read this as an objective reading of the work when in other places this statue is cited as produced for the purpose of enjoyment and titillation. If enjoyment was the intention of the statue for the Assyrian people, then I am to think that this statue represents an ideal figure of its time, rather then an unflattering one. I came across a recent academic paper by Amy Rebecca Gansell on conceptions of Neo-Assyrian ideal feminine beauty while looking for information on Assyrian cultural values relating to beauty. In this paper Gansell references this Assyrian statue of a nude female figure, citing the figure as representing smaller (the statue is slightly smaller then life) and voluptuous female ideals of the time, with round breasts, full hips and thighs. Gansell also notes, Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian detailing of nipples, pubic hair and vulva is understood as relating to fertility. Gansel states that, ‘Ideal feminine beauty, is a modern western construct of scholarly inquiry’ and that ideals for the Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian people are understood as combined values of body ideals and inner morals. I am addressing this because I believe that the wall didactic for the nude Assyrian statue in the British Museum is confusing cultural context and injecting modern western ideals of beauty onto another cultures artifact. As an institution that is currently battling several reparation requests and calling oneself ‘an appropriate custodian’ I would hope that the Museum take an active stand in accurately, professionally and objectively representing the artifacts that you hold and present to the public. I would also encourage the Museum to take reparation requests seriously, as every request that is rightfully honored, the collection may shrink but its public perception will grow and hold a more favorable light. The British Museum is a place of wonder, however questions of proper ownership remain a dark cloud over the institution. My suggestion is that the wall didactic be updated; removing the description of the figure/statue as unflattering and adding the most recent translation of the transcription on the statue’s lower back. This is information that I would hope to find when reading about historical artifacts in the Museum; current, objective, descriptive and relating to the context, culture and time that it was created in. Sincerely,

|

||

_transcription_part_2.jpg) |

||

|

||

Colleen Heslin, Vancouver BC, Canada Sent: March 16, 2016 Dear Madam, I write in reply to your open letter sent by email to this Museum, which has been passed to me as one of the two curators responsible for the new display in the Later Mesopotamian Gallery in which the Assur-bel-kala statue has been displayed. The wording in the British Museum database notes that you quote refers to the ‘enjoyment’ of the people. This derives from the second published translation that you have quoted, that by Professor Grayson, which was published in 1991. Professor Grayson’s translation reads ‘titillation.’ The word in the original Assyrian cuneiform text is æi?ñu or æãñu, a verb which carries a range of nuances, as follows: To laugh; to smile; to be alluring; to act coquettishly and to be anxious (see the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary (1962) vol. Æ, pp. 64-65. The translations ‘enjoyment’ or ‘titillation’ each carry their own specific implications, neither of which seemed to us, in preparing the display and its labelling, to be in keeping with Mesopotamian ideas in general or, indeed, the interpretation of the statue. The following points seemed to us significant: Stone to produce a statue of this size was extremely costly. The cuneiform inscription says that examples of this statue were made for the king for the ‘provinces, cities and garrisons.’ No one can be sure how many this might have involved, but such a national operation was evidently huge. There is no other case of a statue’s being duplicated for distribution throughout the kingdom, and the expense, labour and transport implied means this was something quite extraordinary in every way. Nude three-dimensional sculpture of a woman is likewise an exceptional rarity throughout Mesopotamian history, especially with all the details picked out with such clarity. The whole gives the impression of a specific incident having given rise to a specific response. While ancient concepts of beauty are not necessarily easy to grasp we are of course not blind to the fact that ancient cultures are remote and ancient cultures, but we have a great deal of evidence from Mesopotamian art that beauty in women can never have been exemplified in this statue. Perhaps you will disagree but then, ultimately, this is a matter of personal taste, but against the backdrop of Mesopotamian statuary and likenesses on all scales this statue is unquestionably ‘unflattering’ as it is coarsely finished, heavy, lumpen, distorted and reminiscent of an ape. Grayson’s ‘titillation’ has seemed to us a highly inappropriate motive for this complex operation, being a schoolboy reaction to nudity which simply is wholly out of key with everything we know from the cuneiform world. Much more probable is that the statue was to provoke ridicule, where everyone would recognise who was represented and hoot in derision. This is reinforced by the ‘curse formula’ to protect the statue, which threats snakebite on the guilty party. We have many such formula on conventional works in stone and this strikes a bizarre, and therefore probably comic, response. In conclusion our understanding is that some episode gave rise to this and our own example is the one example of many that has survived down to our own time. We cannot know what prompted the production and distribution of all those statues, although each visitor is entitled to think up a scenario that could explain it. I hope this answers your enquiry. Yours truly, Irving Finkel

Dr I. L. Finkel Assistant Keeper Department of the Middle East The British Museum London WC1B3DG +44 (0)207-323-8310 |

||

| UPDATE!!! | ||

| Email recieved May 13, 2019 from a personal email of another employee of the British Museum who wishes to stay anonymous. | ||

Dear Colleen, You don't know me, but we have an interest in common: the label given to the statue called 'The last woman standing' at the British Museum. I came across your open letter of 2016 recently and wholly agree with your viewpoint.

You will, I hope, be as pleased to know as I was that the museum has recently replaced the older, 'unflattering' card with a more balanced analysis of this statue and the meaning behind it. I attach a photo.

Progress: the wheels grind small, but they grind. Thank you for your work.

all very best wishes, #### ##### |

||

|

||

The Last Woman Standing installed at the British Museum, May 13, 2019 |

||

Comments on the project: The Last Woman Standing, November 10, 2019 This statue opened up an interesting research trajectory into Assyrian notions of beauty and revealed the difficulty of translation over time, language and cultural context. It was interesting how limited my findings were considering my tools of academic text posted online in English, there was one paper that I came across by an American academic, by Amy Rebecca Gansell on conceptions of Neo-Assyrian ideal feminine beauty. Gansell makes specific references to the statue, and the British Museum website provided further information in the online database. The main motivation and interest of this letter and research was to draw attention to the casual use of subjective bias language used to critique the female form. It was unclear if the word ‘unflattering’ was to describe the shape of the body represented or the carving of the statue, or if it was possible to separate the two. After receiving the first response from the British Museum by Dr I. L. Finkel I was infuriated and wanted to continue with a response, but I let it rest. When I received a surprise email in May of 2019 with an image of the new text I was overjoyed, moving from the façade of a brick wall to a view of the dynamics of power shifting behind closed doors. It reveals a generational shift with wider points of view and a greater openness to questions on perspectives of academic work. I would like to thank Alyssa Volpigno and Serrah Russell of Violet Strays for inviting me to do this online project. Big thanks to Shyla Seller for her help editing my letter to the British Museum and neutralizing my sizzling emotions. Thanks to Dr I. L. Finkel of the British Museum for his timely response and a huge thanks to the anonymous worker providing me with an image of the updated text on display and everyone who voiced the need for this update, your email instilled hope for needed shifts and change, thank you! |

||